More Queer Than You Think

In which I ask you to reinterpret a correlation widely accepted between autism and LGBTQ+ identity

Since I quit my job (a story for another time), I have been studying Causal Inference: The Mixtape by Scott Cunningham. I have used it as a handbook for causal inference methods for a few years now, but now there’s time enough at last to sit down and take it cover to cover.

(If for some strange reason you would like to listen to me ponder over causal inference, you can follow me on Twitch. I have been streaming my study time before lunch on weekdays.)

Quick crash course on causality. Normally, if you have some kind of experiment where you were able to randomize the assignment of treatment/control to your units of observation, then you would be able to get the average treatment effect by taking the simple mean differences in outcomes. Most people know that. And most people know that inference on observational data is not going to get you to the same place that experimental data is going to get you because you’re not able to have that random treatment assignment. Well, in some cases you can estimate causal effects from observational data. But, at least thus far in my studying, it seems like it will usually rely on an untestable assumption. So if you’re going to make that leap of faith, you have to really be sure you understand the context in which that untestable assumption is being made. If you don’t — well, you’ll be able to calculate something but whether it has any credibility as a causal effect will rely on your assumptions.

That seems fair, right? In the case where you didn’t do an experiment, sometimes you can recover causal effects and sometimes you can’t, and maybe it will be hard or impossible to know which case you’re in all the time.

So, I thought, maybe I would make an untestable assumption myself and see whether I could estimate something unknowable otherwise. But first, a note about autism, gender, and sexuality.

Autism is correlated with non-heterosexuality and gender dysphoria

In case you’re not familiar, there is a correlation between autism and non-heterosexuality. From Sala et al (2020)’s article, “As Diverse as the Spectrum Itself: Trends in Sexuality, Gender and Autism” the authors summarize the literature:

“In terms of sexual orientation, the overwhelming consensus of recent research suggests that autistic people demonstrate greater levels of non-heterosexual attraction compared with normative data [14, 15, 18, 36, 37]. Higher autistic traits in a Swedish population-based sample (n=47,356) were found to be associated with increased likelihood of self-reported bisexuality or nonnormative sexual orientation [38], and higher scores of self-report measures of broader autism phenotype traits were associated with more same-sex attraction in a sample from the USA [39]. Dewinter et al. [34] compared sexual orientation of autistic men and women from a national autism register (n=8064) in the Netherlands. They measured sexual orientation in terms of attraction to ‘men only’, ‘women only’ or ‘both men and women’ and found sexual orientation amongst autistic men and women varied significantly more than within the general population: A smaller percentage of autistic people expressed attraction only to the opposite sex, and a larger percentage of autistic people did not express attraction to any of the provided categories, resulting a new ‘none of the above’ category added by the researchers.”

It’s pretty awesome that so many different studies (links added to the quote based on the references at the end of the article) have found such a robust result. As far as my read of the literature goes, it was previously assumed that people on the spectrum were asexual and aromantic. It’s only relatively recently that surveys have asked about sexuality, and consistently the autistic group has a higher average non-heterosexual report rate compared to the neurotypical population.

The correlation isn’t only found in sexuality, it is also widely found in self-reported feelings about gender.

“As noted, there appears to be an association between autistic traits and clinically indicated [gender dysphoria]; many autistic people within qualitative studies also describe subthreshold gender dysphoria experiences, such as discomfort or scepticism towards traditional societal gender role expectations [48, 49].

To summarize: non-heterosexuality and gender dysphoria are more prevalent in autistic populations than in the general population across several studies; there is a correlation.

In the face of this evidence, I foolishly ask the question: but what if they weren’t?

Do autistic people conform like neurotypicals?

Before I get to my foolish assumption, I want to spend a little time talking about something that I think is probably conventional wisdom. Autistic people tend not to be as influenced by a need to conform as neurotypicals. The research on this is summarized by Dr. Sara Woods on Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism:

“We know autistic people are sometimes motivated to mask and compensate for differences by copying people around them because of the stigma associated with being different (Miller, Rees, and Pearson 2021; Pearson and Rose 2021; Hull et al. 2019), but research also suggests that autistic people are less affected by social influence (Izuma et al. 2011; Chevallier et al. 2012; Chevallier, Molesworth, and Happé 2012) and are more likely to go against the group (Bowler and Worley 1994; Mailoo 2018; Yafai et al., 2014) and many of our autistic role models show positive nonconformity (Dupere, 2017). While autistic people’s nonconforming behavior is often devalued (Sasson et al. 2017; Bolton, Ault, and Meigs 2020), positive nonconformity can effectively transform groups and organizations (Jordan, Fitzsimmons, and Callan 2021), and can be quite literally life-saving (T. Beran 2015).”

Note that I could not find the Mailoo article in the article’s references or through a Google Scholar search; otherwise I provided links where possible. In any case, I don’t think it’s too controversial to ask you to consider that folks with autism and folks without autism have different levels of sensitivity to social influence. In fact, if one were to claim that sensitivity to social influence is independent of neurotype, I think that would be considered a strange assumption.

So why do we assume that folks on the autism spectrum are as likely to be closeted about gender and sexuality as neurotypical folks?

If openness about non-normative sexuality or gender is a function of social influence, then you should question whether the control group is as forthcoming as the autistic group in the studies I mentioned in the previous section.

This is why I have come here today to ask:

What if autism and LGBTQ+ identities are independent (in spite of known correlations)?

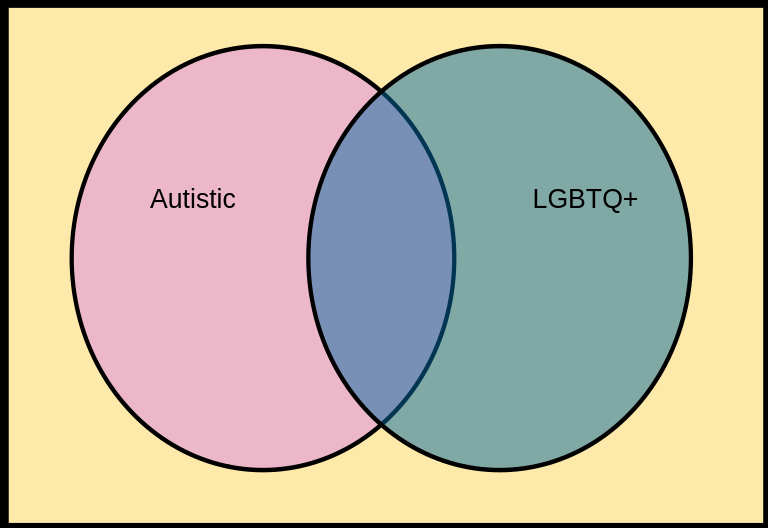

Please consider the Venn diagram of Autism and LGBTQ+ identity.

As a reminder, the way these types of diagrams work, if you belong to the labeled set, you’re inside the circle, and if you don’t belong to the labeled set, you’re outside the circle. So in this division of identities for the world, there are four combinations of identities that can be found on the diagram:

Autistic and LGBTQ+: in the intersection of the circles

Autistic and non-LGBTQ+: in the left circle not in the intersection

Non-autistic and LGBTQ+: in the right circle not in the intersection

Non-autistic and non-LGBTQ+: outside both circles

Alright, so if these two identities were independent, what would that mean? It means the additional information of one identity does not change the probability of a person holding the other identity.

This is read as, the probability of a person having an LBGTQ+ identity conditional on knowing they have an autism identity is equal to the probability of a person having an LGBTQ+ identity (in the general population).

But that isn’t what all those studies in the first section said — right?

Technically, those surveys could only talk about self-reporting; folks who both identify as LGBTQ+ and are open about it. My suggestion is to reinterpret those statistics as the truthfully revealed estimation of the rate of LGBTQ+ identity in the general population because folks on the spectrum are more likely to be open about their non-conforming identities than the general population.

Formally, I’m asking you to consider the following to get a lower-bound:

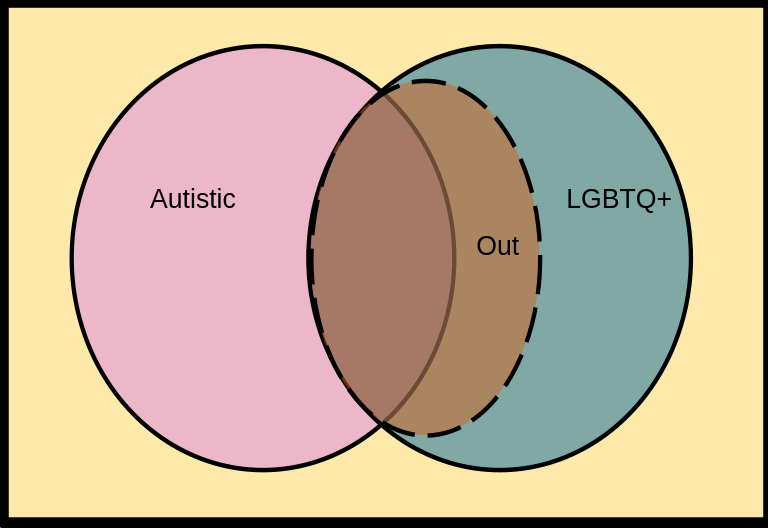

Which would be visualized as follows:

This represents a world where all Autistic and LGBTQ+ people are also Out, but only some non-Autistic LGBTQ+ people are Out. Note that Out is a subset of LGBTQ+; you can’t be Out unless you’re also LGBTQ+. ‘Out’ in this case really refers to being able to reveal LGBTQ+ identity in a survey or study.

In other words, if we have surveys that say 9% of the USA self-identify as having LGBTQ+ identity, but studies of autistic folks find 15-35% LGBTQ+ identification rates, then you should consider the statistic from the autistic population as an estimate of the actual underlying LGBTQ+ population and that somewhere between 6-26% of the general population is not revealing their identity to pollsters.

This is easily derived from my two — untestable! — assumptions based on unobservable data.

Now, I mentioned this was a lower-bound estimate. That’s because if not all autistic people with an LGBTQ+ identity are ‘Out’, then the LGBTQ+ identification rate among autistic people is actually higher than the 15-35% reported. So you don’t need to believe all autistic LGBTQ+ people are disclosing their identities in these polls and studies.

So, what do you think? Have I convinced you that the correlation between autism and LGBTQ+ identity is being misinterpreted?

Bonus: more reasons to believe

Gen-Z LGBTQ+ identification rate falls in my autistic population-based estimate for the general population

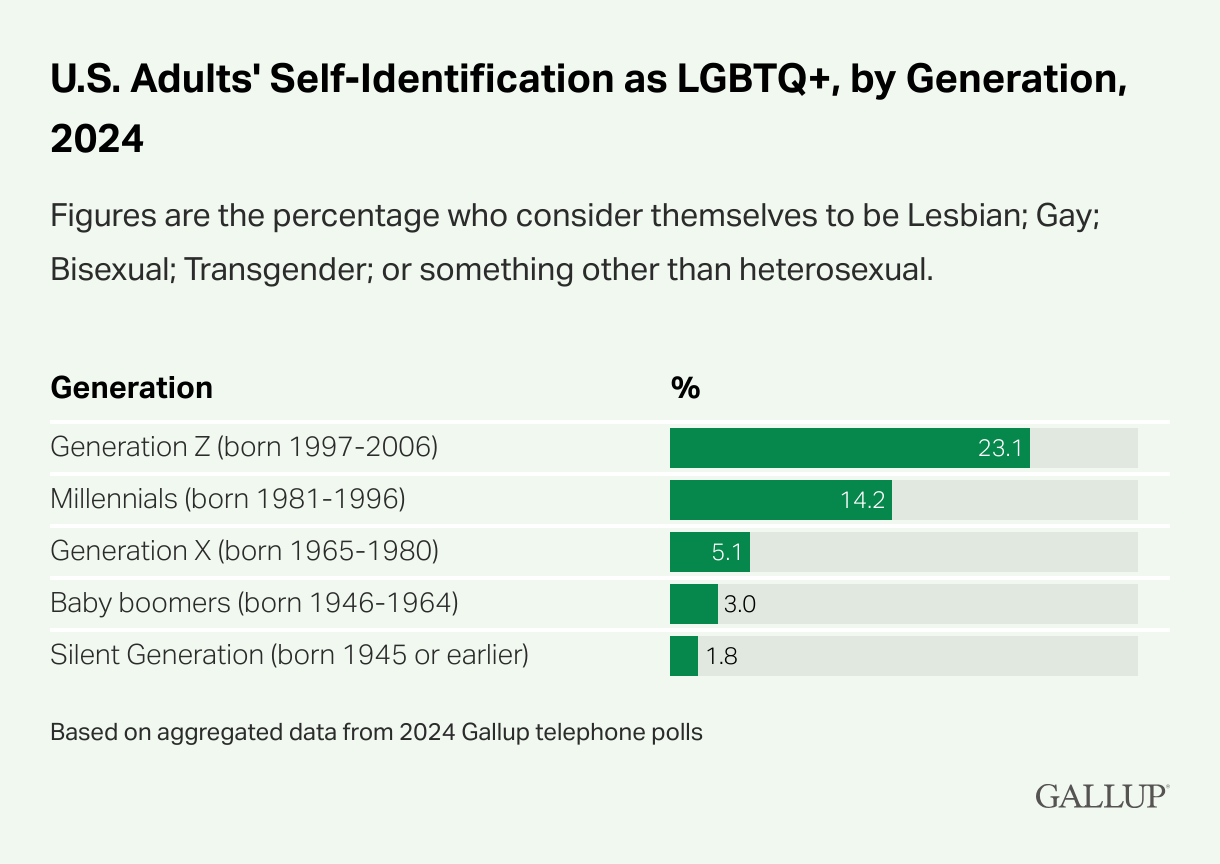

An interesting statistic I found in this cursory research is a Gallup breakdown of US Adult Self-Identification as LGBTQ+ by Generation as of 2024.

In this chart, each newer generation has a higher LGBTQ+ identification rate. Do you really think successive generations are getting less heterosexual? Or do you think the social stigma of being open about an LGBTQ+ identity is lessening? Averaging across the whole population you get the 9.3%, but isn’t it interesting that the latest generation has an identification rate that falls in the range estimated among the autistic population?

This reminds me of the graph of left-handedness over time.

Left-handedness is also correlated with autism

The source of the chart seems to be paywalled, but credit to Chris Ingraham of the Washington Post for his “The Surprising Geography of American Left-Handedness” that shows a rise in left-handedness from around 3% in the 1910s to around 12% in 1960, then staying at that plateau through 2000. You can view the graphs here and a summary of the article and its sources here. There was strong social stigma against being left-handed. I wonder whether there was a correlation between autism and left-handedness?

Paraskevi Markou, Banu Ahtam, and Marietta Papadatou-Pastou, in Neuropsychology Review, back in 2017, published, “Elevated Levels of Atypical Handedness in Autism: Meta-Analyses” and found (according to the abstract)

“Meta-analysis set 1 found that individuals with ASD are 3.48, 2.49, and 2.34 times more likely to be non-right-handed, left-handed, and mixed-handed compared to typically developing individuals, respectively. Meta-analysis set 2 found a 45.4%, 18.3%, and 36.1% prevalence of non-right-handedness, left-handedness, and mixed-handedness, respectively, amongst individuals with ASD. The classification of handedness, the instrument used to measure handedness, and the main purpose of the study were found to moderate the findings of meta-analysis set 2. Meta-analysis set 3 revealed a trend towards weaker handedness for individuals with ASD.”

So, yes, left-handedness and autism are correlated. Note also that we have a generational aspect to this issue as well. The estimate of 12% of the general population being left-handed may be due to older people who otherwise would have identified as left-handed, instead were forced to identify as right-handed from an early age. Instead, I would suggest considering the autism population-based estimate of 18.3% as a better estimate of the general population’s left-handedness.

Lack of a biological explanation

In “Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: A narrative review,” Anna I. R. Van Der Miesen, Hannah Hurley, and Annelou L. C. De Vries examine the evidence linking autism and gender dysphoria. They find the correlation that we’re familiar with by now, but their assessment of explanations is most interesting to me:

“Various underlying hypotheses for the link between GD and ASD were suggested, but almost all of them lack evidence.”

In the article, they break down the hypotheses into three camps: biological, social, and psychological. The biological hypothesis sounds to me, a layperson, like sexist baloney. It’s called “extreme male brain theory” and relies on a gendering of brain functions that I think should be questioned. The review didn’t find research consistent with this theory. A related biological hypothesis is related to testosterone exposure in utero and birth weight, but again it wasn’t like there was research providing a slam dunk here.

“At present, there is no evidence for specific risk factors that might be involved for either GD or ASD and the aetiological factors that are suggested are speculative.”

That’s the latest research on the T part of LGBTQ+. As for the LGB, I’ll avoid going down a further rabbit hole and just quote Wikipedia:

The relationship between biology and sexual orientation is a subject of ongoing research. While scientists do not know the exact cause of sexual orientation, they theorize that it is caused by a complex interplay of genetic, hormonal, and environmental influences.[1][2][3] However, evidence is weak for hypotheses that the postnatal social environment impacts sexual orientation, especially for males.[3]

Biological theories for explaining the causes of sexual orientation are favored by scientists.[1] These factors, which may be related to the development of a sexual orientation, include genes, the early uterine environment (such as prenatal hormones), and brain structure.

And contrary to US policymakers’ beliefs, I am unconvinced that vaccines or Tylenol are the causes of autism.

All I’m saying is, if you’re trying to find a biological explanation for the correlation between autism, gender dysphoria, and non-heterosexuality, maybe consider that these could be completely independent identities. The correlation could arise because neurotypicals are less open to sharing with researchers and pollsters what autistic individuals are more willing to share.

References

Markou, P., Ahtam, B. & Papadatou-Pastou, M. Elevated Levels of Atypical Handedness in Autism: Meta-Analyses. Neuropsychol Rev 27, 258–283 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-017-9354-4. Downloaded 2025-12-12.

Sala, G., Pecora, L., Hooley, M. et al. As Diverse as the Spectrum Itself: Trends in Sexuality, Gender and Autism. Curr Dev Disord Rep 7, 59–68 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-020-00190-1. Downloaded 2025-12-12.

Van Der Miesen, A. I. R., Hurley, H., & De Vries, A. L. C. (2016). Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: A narrative review. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1111199

Woods, Sara. Autistic People and the Power of Positive Nonconformity. Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism. https://thinkingautismguide.com/2023/09/autistic-people-and-the-power-of-positive-nonconformity.html. Downloaded 2025-12-12.